When I was in grad school, I served as the teaching assistant for a lab course in optics and acoustics. It was a service course that our Physics Department offered to the School of Architecture.

Part of the course involved colorimetry, a technology that represents color as a set of coordinates in a color space. We’re all familiar now with red, blue and green, and what we can achieve with our digital cameras, but these devices had not yet come into common use.

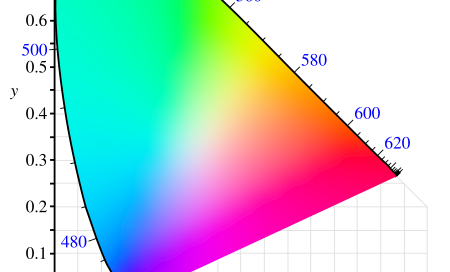

We taught the students how to mount samples in front of lamps, and how to use a spectrometer to measure the energy present at different wavelengths in the reflected light. They would then compute the chromaticity coordinates for the surfaces being studied, the x and y on the colored diagram associated with this post, which comes from the standards developed in 1931 by the Commission internationale de l'éclairage (CIE).

Did the “leaf green” from the paint manufacturer really match the spectrum of an actual leaf? Or would they look different under different types of light?

The intent was to empower the architects in their use of color. On a big project, building materials have to be specified and purchased in bulk. The architect might not be doing a spectroscopic analysis on every can of paint, but knowing how to do it is helpful, as is knowing the legal process used to resolve disputes with manufacturers and suppliers.

An individual artist working with paint on paper can judge its effect immediately. Architects and others working on a larger scale must inevitably be users of systems, and therefore need to be judges of their relevance and quality.

I’d like to say that I was a perceptive young man who grasped this right away, but I wasn’t. The idea of “connecting people with systems” was first suggested to me by an outplacement consultant later in my career. He gave me a number of tests and found my coordinates in “personality space”. I learned, for example, that my Myers-Briggs type was “ENTP”, and that my Strong Interest Inventory aligned me more with traders than bankers, which probably explains why I did so well at NYMEX and CME Group (although I always worked in execution services as opposed to clearing).

Recently, though, I asked myself when and where I had first thought about “connecting people with systems”. It’s obvious that everyone who works in applied science must do this to some degree. Math is a system. Physics is a system. They ought to empower the people they connect.

Yet all too often they don’t. I frequently meet people who were turned away from math and science in school, just as they were turned away from many other things that would be useful to them, including the skills needed to collaborate with other people in the largest system of all.

I’m not going to say that the architecture student with a light meter is our only model for the Person of the Future. Nor is “connecting people with systems” the only way to do good in the world. But it’s worth thinking about, especially in these days when systems are used to divide people, as opposed to uniting and empowering us.